SOFemArt Saff

1/10/2026

•

5 min read

Some artists choose a medium and others choose exploration. Moving fluidly between architecture, visual art, sculpture, and photography, Emily De Lima builds worlds from sketches, discarded materials, and spontaneous ideas. Now based in Queens after graduating from Cornell University’s architecture program, Emily is shaping a practice that refuses limitation and thrives on curiosity. In this Q&A, she shares how experimentation guides her process, why “jack of all trades” feels like a compliment, and how every piece, whether a small collage or a building-scale concept—begins as a prototype with room to grow.

Q: You’re a multidisciplinary artist with work spanning architecture, visual art, sculpture, and photography. How do you decide which medium becomes the best for a particular idea or moment?

Emily: Since I’ve never been able to stick to just one medium, I’m constantly experimenting. I like to pick things up and figure out how they work and what they can become. Sometimes an image flashes through my mind and I sketch it out, and those usually turn into paintings. Other times, I just look around wherever I am and see what materials I already have lying around. I love using things considered scraps or trash. I’ll start cutting things out and assembling them, and an idea grows from there.

Everything is a prototype. I’m just trying things out, seeing what works. Smaller pieces become whole, whether that’s the scale of a painting or a building. They say, “A Jack of all trades is a master of none, but oftentimes better than a master of one.” I think there’s something beautiful about not mastering just one thing—staying curious and letting the process guide where the work goes.

Q: Much of your practice focuses on origin and cultural sensitivity. How has growing up as a Brazilian woman in America shaped the way you interpret space, material, and narrative?

Emily: I think a lot about humans versus shells. How the outer layers we carry affect how people see us. These shells appear on many scales; in the spaces we occupy, the clothes we wear, even the ways we carry ourselves. Often, they get in the way of us truly seeing each other as human.

I’ve always been a bit of a nerd, but because I didn’t fit the typical visual stereotype, I often felt very “othered” in the spaces I’ve occupied. At Brooklyn Tech, the specialized high school I went to, only 7% of the student body was Hispanic/Latino while I was there, and I was frequently overlooked or stereotyped. At Cornell for university, I was again a minority and I faced similar assumptions. The way I look has affected how seriously people, especially men, have treated me, and I’ve had to work a lot harder to be heard.

I poured these experiences into creating “EXOTIC!”. This ended up being my first exhibited piece, where I drew a parallel to the Brazilian Spix’s blue macaw. The macaw was targeted for its striking blue color and rarity, making it a prized trophy in the illegal bird trade. It was captured and admired, but rarely understood. Their beauty essentially became their downfall, collectors captured them faster than the population could recover, pushing the species to the edge of extinction. I have often been treated in a similar way, as a shiny object that people want to be seen with, but not listened to.

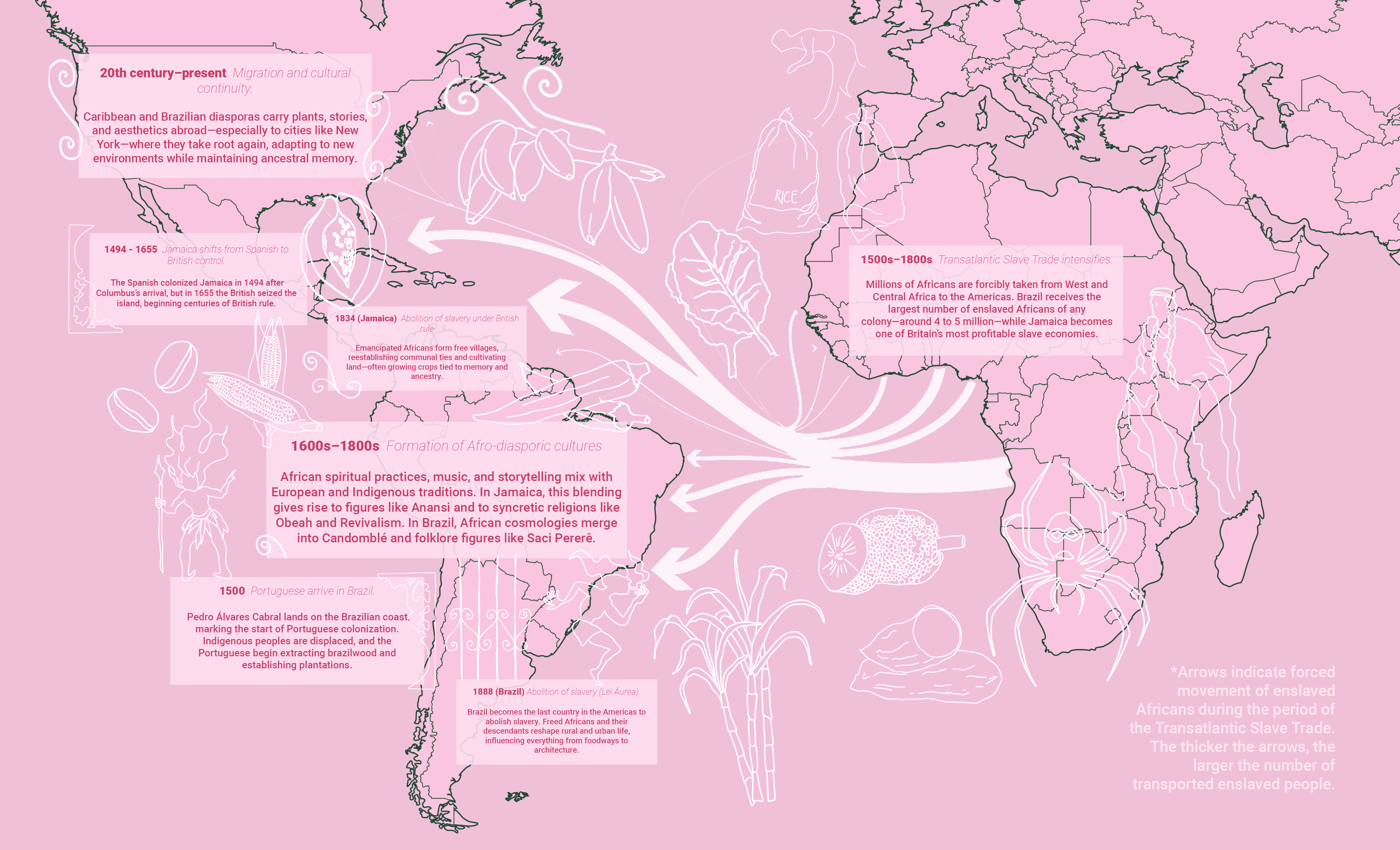

Q: Your installation “What We Grow” investigates the lasting effects of colonization across Brazil and the Caribbean. What compelled you to take on this history, and how did the collaboration with Cornelius Tulloch shape the project?

Emily: “What We Grow” really started with an architecture option studio I took at Cornell Tech in 2023. We worked closely with Ena McPherson, a Jamaican woman who was a pioneer in the urban gardening movement in East New York. Getting to know her made me notice how much Brazilian and Jamaican culture overlap. That pushed me into researching how plants, traditions, and knowledge moved through the transatlantic slave trade and ended up forming the worlds we grew up in. The similarities weren’t coincidence, but were the result of people carrying their worlds with them under unimaginable conditions.

The collaboration with Cornelius Tulloch came naturally out of that. Cornelius was a former student of my professor, Peter Robinson, who’s career path blended art and architecture as I was aspiring to do. Peter saw the overlap in how we both think spatially and visually and encouraged the connection.

I applied to a grant opportunity through my school and was awarded to further the research I began in that studio. This culminated into “What We Grow,” a public installation that took place in Tranquility Farm in Brooklyn, NY.

Q: When you examine how knowledge is passed through craft and tradition, how do you see your own artistic practice contributing to that lineage of storytelling?

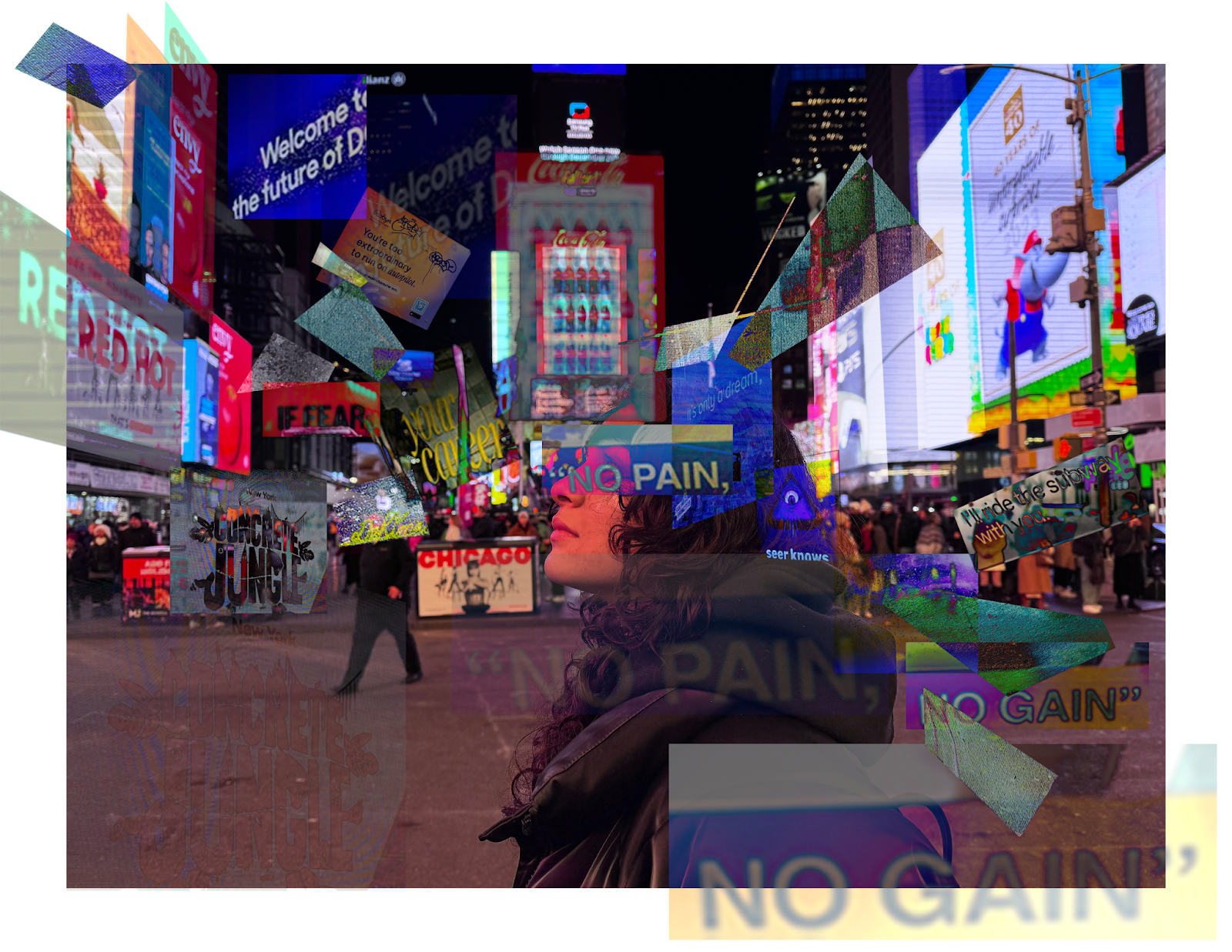

Emily: As times change, so do crafts and traditions. Existing practices are added to and transformed with new ways of making. For me, being Brazilian-American adds another layer to this as I’m constantly mixing influences from my Brazilian heritage with the culture I grew up with here in NYC. I’m particularly interested in how being an artist has also significantly shifted in a digital, hyper-capitalist age. It’s no longer enough to just be a skilled painter, you also have to build a presence, navigate both real-life and digital spaces, and find ways for your work to resonate in an oversaturated market. I want to make work that bridges traditional art and digital platforms.

Right now, I’m working on a short film where I take elements from physical pieces and adapt them for a digital video platform, exploring how craft and storytelling can evolve while still carrying the same lineage of care and knowledge.

Q: With a background in architecture, how does spatial thinking influence the way you build worlds whether as installations, images, or objects?

Emily: Again, I think of everything as pieces that fit together to form a whole. From the screws that hold a structure together, to the columns that support a building, threads that keep fabric intact, layers of paint on a canvas. Every element matters, and everything connects in ways we don’t always expect. My process of building, testing, and letting the idea dictate its form comes directly from thinking like an architect, even when the work ends up on a flat surface.

Q: What questions are currently guiding your creative direction as you move into this next chapter of artistry?

Emily: I grew up in a very Catholic household and went to Catholic school from pre-K to 8th grade. I was always the kid asking too many questions, and that curiosity wasn’t really encouraged. For a long time, that pushed me to reject religion altogether. Now, I’m in a place where I’m reevaluating a lot of it. I’ve studied bits of different belief systems, and I’ve started building my own understanding of spirituality, one that mixes my appreciation for science with the way I see nature and the universe function.

The questions guiding me now are about how humans create meaning, how we inherit stories, and how we rewrite them. I’m interested in how identity is shaped by the things we’re taught versus the things we discover on our own. Those themes have already started appearing in my recent work, and I think they’ll keep leading me forward.

Rapid fire: One material you could work with forever — go!

Emily: Spray paint! I love the messy drips and how you can play with splatters and flicks. It lets me work fast, and experimentally, but it also forces me to adapt and embrace accidents.

Q: What are you most excited for audiences to feel or discover when they encounter your work at the March 2026 SheROCKS showcase?

Emily: I’m excited to finally push my way into the art world. I graduated just last May, and since then I’ve been pouring myself into making new work and getting it out there. I’m looking forward to giving the audience a glimpse into my chaotic brain. I have a million ideas and I can’t turn them off.